Introduction

Although I have only worked in an NGO for three weeks, I have already noticed a key issue which has been reinforced by conversations with people who work in NGOs and aid organisations. The issue is evaluation and monitoring which aims to improve the overall performance of aid organizations and enable donors to make informed decisions about where to put their money. During my Bachelor programme I had already engaged with this issue from time to time on an academic level. I thought that if these issues are common knowledge, or at the very least academic knowledge, then aid organisations should be in the process of addressing them, right? The short answer is no.

(I know in my last post I said I will try to keep posts shorter and less theoretical but this did not work out with this one. If you have limited time or are less interested in the analysis of the issue you can jump straight to the summary of criticism and read from there.)

Limits of Output and Performance-based Evaluation

How limited the evaluation in aid organisations is, became clear to me in two conversations. The first one was in a restaurant in Amman, where I was talking to a friend who has been working in major aid organisations for several years. After some small talk and ordering food, I asked how the organisation she currently works for, approaches evaluation and monitoring. She said that it moved from output to performance-based evaluation and considered that to be sufficient to ensure a high quality of projects. Output based evaluation is the easiest but also the least reliable way of doing evaluations. The idea is that the quality of a project is measured by the numbers it produces. Consider the example of a workshop on female empowerment and confidence. To assess the quality of the workshop, the duration of the course and the number of participants would be measured. A long workshop with a high turnout would be considered of high quality. It is however possible that the participants are disempowered and feel less confident after the workshop, yet the output-based evaluation could still consider it to be high quality because a lot of women showed up. The next level of evaluation is the performance based one. It still measures the number of people participating but puts a focus on whether the goals of the workshop have been achieved. My friend outlined to me that participants are often given a survey before and after the workshop which asks them about what they learned and how they feel. The results are then compared to the goal of the project and if they match, the project was of high quality according to the performance-based evaluation. She added that sometimes participants and beneficiaries are invited again up to a year later to evaluate long term impact.

It is obvious that performance-based evaluation is better than the simple output-based one but there are two key problems. First is the question whether the participants are good in assessing whether they benefitted from a project or not. For simplicity’s sake let us assume that they can do so for now. Then the second issue is that the person who organizes the project is the same also gathers the data and conducts the performance-based evaluation. This creates an obvious conflict of interest. If I organize a project, I want it to be successful and potentially my job depends on my projects being successful. Thus, I will at the very least be subconsciously biased when creating a performance-based evaluation. Worst case I will consciously conduct the evaluation in a way that is bound to give me better results or simply falsify and misinterpret data. Either way bad projects might get funding again and again because the person who conducts them is put in a position where they benefit from doing so.

Time, Money, and Evaluations

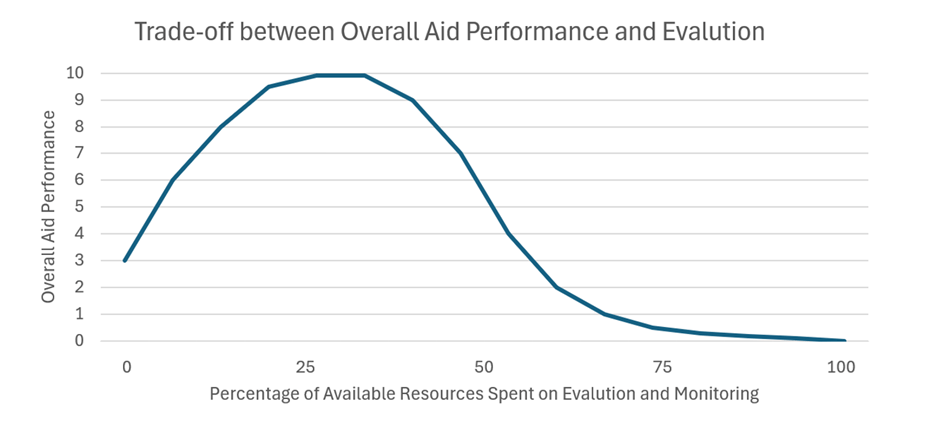

The issue became even clearer when I was discussing the same issue with a colleague in the office. I asked how the organization we work for conducts evaluation. She explained to me that this depends a lot on who is providing the funding. Some donor organizations simply require an output-based evaluation, but most require a performance-based one, again conducted by the person who is organizing the project. When I asked her why they do not always conduct at least a performance-based evaluation she replied that this takes additional time and effort which is unaccounted for in the budget that a donor who only requires an output-based evaluation is providing. This, in general seems to be a big problem. Proper evaluation takes time and money. NGO’s and NPO’s tend to have little of both and prefer to spend it on projects rather than evaluation. The graph below illustrates this the trade-off between using resources on evaluation instead of the projects themselves, working with the assumption that there is a limited amount divided between the two. The trajectory is how I would expect it too look but and the numbers are entirely made up. They only serve to illustrate the point that there is an optimal allocation of resources between the projects themselves and evaluation and monitoring. In the case of this Graph, it is around the 30% mark. Before this point, evaluation improves projects and the allocation of funds to an extent where it offsets the fewer resources available for the projects. After the 30% mark any additional money spent on evaluation would be better spent on the projects themselves if the goal is to improve the overall performance of aid.

In big projects part of the funding is intended for independent evaluation and monitoring. By big projects I mean ones that costs millions and are often funded by states. Apart from hiring independent evaluation, which is done at the end of the project, they also conduct monitoring. Monitoring means to assess the quality of a project while it is being conducted and propose improvements that can be immediately implemented. Since there are significant funds allocated to evaluation and monitoring and it is conducted by an independent organization the quality is high. There are some issues, however. First, of course is the cost. Smaller organizations will find it impossible to conduct evaluation and monitoring of a similar quality. This leads to the second issue. If big projects rely on smaller organizations to realize them these small projects will lily provide unreliable evaluations of their small-scale projects. Even good monitoring and evaluation upper levels of organisation will not be reliable if the sources of information are not.

Short Summary of Criticism

To summarize what I outlined so far, there is several levels of evaluation and monitoring which aid organizations use to assess the quality of their projects. The core idea is that by measuring the impact of projects well, resources can be directed to them which should improve the overall quality of aid. Output-based evaluations is the first and simplest way to measure impact. It mainly considers the number of people who receive aid but not the quality. Thus, it could consider a project with a high turnout, but which does the opposite of what it intended as successful. It is a crude and inaccurate way to measure performance. As a response to these issues aid organizations started to conduct performance-based evaluations. These measure not only turnout but also if the project achieved its goals, typically through surveys, completed by the beneficiaries. The key problem with this approach is that the evaluation is conducted by the people who organized the project which leads to a clear conflict of interest. The quality of any evaluation can be improved by having an independent agent conduct it, however that is expensive and tends to be possible only for projects with large funding. There is also monitoring which is conducted while the project is implemented and enables feedback loops that can improve the project before it is finished. Again, this is better if done independently and it is probably the most expensive since it is conducted throughout the project.

Independent Monitoring and Private-Sector Methods (Outlook)

This all is not to say that we should not donate to or support aid organizations. Instead, this aims to give some ideas for improving the quality of projects that NGOs and aid organizations organize. Given the previous criticism I see two solutions. The first one is straight forward and hinges on two questions. First, can the overall quality of aid and NGO work be improved if more money is spent on evaluation. If the answer to the first question is yes, then the second one is how much money should be spent on evaluation. Conducting evaluations costs money which is then not available to realize more projects. At some point there is too much money put into evaluation and too little into realizing the projects and the overall performance of NGO and aid performance. It is a balance to be struck between spending enough money on evaluation to ensure the overall quality of aid while not spending too much to the point where many projects cannot be realized because the money is spent on evaluation. To improve evaluation, an independent monitoring and evaluation NGO might be beneficial. It will solve the issue of conflict of interest and could secure its own funding so that it can provide its service for free to smaller organizations. From my research so far, I was not able to find an organization like this, so I invite you to research this further and give it a shot.

The other way to improve overall performance by improving evaluation and monitoring is to introduce methods from the private sector. There are two keyways in which performance is evaluated and monitored in the private sector. The first is by the consumer who can choose not to buy a product or buy an alternative one. The consumer tends to have little insight into the inner workings of the producer, but they can test the final product and buy it or not. This is a way of evaluating the quality of a good, because if people consider it low quality, they will not buy it, and it will disappear from the market. This is difficult to realize in the context of aid because the beneficiaries often cannot choose between aid providers. A trend that is picking up in aid organizations right now is to consider them not as beneficiaries but as clients which shifts the relation between the two. A client has a position of power from which they can, for example claim that the service they were promised was not provided and can demand compensation. A beneficiary cannot do that. How this works in practice takes some more thinking on my side but I think it is an interesting change in paradigm to improve aid. The other way in which methods from the private sector can improve the evaluation is by imaging donors as investors. A company is required to provide information about the performance of the company and its inner working. They all have significant influence on the direction of the company. In the case of aid organisations donors receive little to no information if their contribution achieved or changed anything. If they were informed about the impact of their donations, they would likely start to focus their donations (or investments) into the most successful projects. The return on “investments” into aid organisations would not be dividends but instead the aid that these organisations can provide with your money.

I know I promised in the last post that I want to change my content towards shorter and less theoretical discussions, and I failed both goals in this text. So, I want to reward the fact that you manged to read this far by finishing with an out-of-the-box idea to keep this fun. If we consider doners more as investors and dividends as the aid that the aid organisations can provide with your money, then what could be a way to simulate the stock exchange? I think it would be an interesting concept if by donating once or on a regular basis to an aid organization, doners could receive shares in it. If shares are limited, then the value of them will depend on demand. As mentioned before the dividends for aid organization is not money but the aid that they can provide. Thus, the better the aid that an organization can provide per dollar they receive the, the higher the dividend is. Following the free-market rationale the higher the dividends the higher the demand for the shares and thus the value increases. Maybe you are starting to see the benefit of this now. Imagine you buy a share in UNICEF now for 50$ and in the following two years UNICEF’s performance improves significantly. The demand for UNICEF shares thus increases because their “dividends” are increasing. Consequently, the share that you bought for 50$ is now worth 75$ due to increased demand. So, if you sell it now, you could make 25$ by selling the share, not accounting for inflation. This system could ensure additional funding for aid but now donors have a monetary incentive to invest in organizations which they expect to perform well. Money would be directed to well performing organizations which would be another way of evaluating their quality because there is money in it now, which tends to improve the quality of evaluation. This idea needs some more thought of course but still I think it is quite intriguing and I might explore it in the future.

Leave a comment